Para español, leer debajo de las imágenes…

The New XXI Century Urbanism in Developing Countries. Case Study: India, by Alfredo Munoz.

We are immersed in a society that has rapidly changed from the culture of industrialization characterized by perfect, categorical, and rigid solutions; to another based on a precarious, fast, fluid, and shapeless context, archetypical of the Society of Information. Globalization has accelerated the process of social transformation and, therefore, of the public space in the city.

Today’s’ habitability is spent in the places that Augé called the non-places, that is, architectural and psychological spaces that somehow are not ours and that are not able to be colonized. In urban language, they are unregulated urban spaces, “free of domination,” as described by Habermas, in which the new society can see itself better reflected. This concept of public space is even more noticeable in the urban environment of main Developing Countries (BRIC), where the speed of execution, financial pressure, poor regulation, and the “momentum” of growth creates multiple brand new unregulated spaces in terms of typology and urban structure.

India has some features shared by other Eastern countries, but, at the same time, shows another set of specific characteristics that must be analyzed in more detail to understand the new urban structures, and the infrastructures of the country.

Hand in hand with the social-cultural change resulting from globalization, we find the economic engine as the basis for such transformation. That is why it is crucial to analyze the economic assessments to understand the urban structures in developing countries, even more, if we take in account that in such countries, the economic pressures are the ones that generally promote, organize, and structure the new urban spaces and the city’s infrastructures.

In the case of India, we can observe that the topology, conceived as the science of connectivity, is getting closer to explain the new urbanism, where the importance in architecture is not the objects by themselves, but the space-time relationships between them.

In the urban environment, this topology leads to sponge-like organizations, concentrated, and vast space that prompts different relationships between the natural and the man-made environments, relationships that we can hardly explain with the “background-figure” gestalt terms.

The European model of a city and public space gives way in India and a large number of BRIC to another kind of organization more open, less structured, where the separation line between public space and infrastructure becomes thinner, even merging.

Urbanism as a cultural reflection. The Asian Context:

The study of India, as part of the Asian continent, reveals several shared features in the Asian culture that can greatly help to understand the culture of India.

Of the 21 civilizations that have existed in the World, according to Toynbee, only six remain today: three Oriental (Chinese, Indian and Japanese), the Occident, and the two cultures derived from it (Russia and Islam). Chinese and Indian Civilizations are the oldest, enduring uninterrupted for thousands of years. The Occident culture is born, according to the same author, around 700 BC, as a result of the Hellenic culture, while the rest appear after the year 1000 AD.

When we compare culturally speaking, the Judeo-Christian-Muslim vision and the Asian conception of the world, the differences between the first three seem nonexistent. Given the way almost the opposite of understanding the reality of East and West, we could say that we are in front of two great ancient cultures in the present.

The Occident has grown outwards, the Orient inward. Some have reached the moon while the others reached distant states of consciousness. One culture is linear, centrifugal, and progressive; the other is conservative and concentric.

From a cultural point of view, time is cyclical in the east and linear in the west. For the West, there are absolute truths establishing the pure and abstract concept of opposite terms. To the east, everything is relative and complementary. For the Eastern cultures, the reality is part of a great interrelated balance, where opposed doesn’t mean contrary. For Western mentality, educated in the Cartesian dualism and in the Aristotelian logic, it is really hard to understand these nuances.

In the East, there is the concept that harmony resides in diversity, while the reality is a constant flow of change. The possibility of improvement takes place through introspection. By contrast, Occident needs absolute truths, and the concept of harmony is related to a single truth. It requires immutable essences, solid, rather than the Oriental mind of the dynamic stream. The West prefers invasion over introspection.

To the east, the seemingly opposite are different states of the same process, and to get there, the development must be circular, not linear like in the West. Occident adopted the Jewish myth of linear creation to explain reality. On the other hand, the East does not separate the creator from creation, setting up a spiderweb-like organization system.

Urbanism as an economic-cultural reflection. The developing country context:

Among the so-called big emerging countries BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China), we can find very specific characteristics in India.

Political stability, linked to democracy (India is the most populated democracy in the World), the high level of English of the citizens, the high quality of education in Indian universities, the cultural skills related to technology services (IT), and the fact that governments are open to foreign investment, have been some of the key elements to understand the “economic miracle” that just occurred in India in the last decade.

The growth of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in India, along with other features that we will mention later, lead many analysts and experts, including Goldman Sachs, to predict that India will be the second economic power in the World by the year 2050.

From a demographic point of view, what for years was a big issue, today is becoming the best asset: With a population of 1.2 billion people and an annual population growth of 1.4%, experts estimate it will exceed the total population of China by the year 2035. This population, with an increasing percentage of them belonging to the middle classes thanks to the economic growth of the country, brings with it a very high demand for workforce, services, infrastructure, and products. The growth of the middle class during the last decade has turned India into the country with the largest middle class in the world.

Also, India has a very young population structure if we compare it with countries like the USA, China, or Europe, where 650 million people are younger than 25 years. That assures a very large base of production for the next 50 years.

To this reality couples with the fact that currently, only 25% of the population lives in an urban environment, so it is predicted that a large migration movement from rural to urban areas will keep happening, due to the large demand of highly skilled workforce in major cities, more if we think that a big part of the country’s productive structure is associated to services (call centers, IT industry, light industry, etc). This reality shows that large urbanizing processes and big development of infrastructures are still to come.

From the standpoint of urban growth, currently, we have three types of cities:

Tier 1. They are cities currently very dense, with a lack of undeveloped areas for expansion. This cities are mainly Mumbai or Delhi NCR.

Tier 2. They are cities with very active housing developments and with some more areas to expand. Bangalore, Hyderabad, Chennai, Pune o Kolkata belong to this group.

Tier 3. They are emerging cities with high growth potential, where the expansion is taking place in a slower and more controlled way. Chandigarh, Jaipur, Nagpur, Ahmedabad, Mysore o Goa belong to this group.

While many elements turn India into a country with high growth potential, some of them already summarize before; other features pose great challenges for the country to maintain the current high levels of economic, urban, and infrastructural growth.

The rigid social organization, inherited from the caste hierarchy, sets a very stratified population in India, turning down often the potential for the individual growth that is typical of other developed countries and creating big economic and social differences. Also, the opacity of the system, the high levels of corruption, and the vast bureaucracy of such a large country creates loopholes, deregulation, submerged economy, and makes hard for the foreign investment to operate, just to mention some of the direct consequences of the other reality of the country.

As it happens to a social level, from the urban and infrastructural point of view, India has strong contradictions. In India, we constantly find large spots of development surrounded by totally impoverished and neglected areas. These differences are even more noticeable in cities included in Tier 1 (Mumbai and Delhi NCR).

Since the beginning of the economic boom of the early ’90s, the investment in infrastructure has been segregated of an equally fast economic growth, creating an overflow in the infrastructures and the urban system of the country.

The small economic resources of public administration, their slow decision-making associated with the large bureaucracy, and the financial pressure related to the general growth of the country have made that the private sector conducted most urban and infrastructural developments.

This fact of the development promoted by the private sector, along with the fast performance and other intrinsic characteristics of the country, is what is generating a new city and infrastructure development completely original in the world, model which offers a big interest for the economical as well as the typological analysis.

Planning and Infrastructure in India. Typological study:

Among the motors of urban generation, large scale infrastructures, and architecture, we can include the following:

– Slum regeneration (slum areas) in large cities primarily for residential use.

– Creation of mixed uses townships, in many cases called SEZ (Special Economic Zones)

– Government grants to the private sector through BOT systems (Build, Operate, Transfer)

The first one occurs in large cities Tier 1, especially in Mumbai, and consists of a program of regeneration of large slum areas near downtown. Due to the scale of these interventions, they are divided into micro sectors with public regulation that later are developed by the private sector. Dharavi, in Mumbai, is one of the best examples of this typology which presents a deep social involvement and a big urban and infrastructural impact on dense Indian cities.

The second one occurs in cities from Tiers 2 and 3, where there are large free undeveloped areas in the outskirts of historic cities. New developments in these areas create new ground-up, self-functioning townships. In some cases they are called SEZ, as the government provides fiscal advantages to develop urban development associated with the productive sector, mainly technology services and biotechnology. Those production complexes (Processing zones) are usually surrounded by residential and commercial. The land size of these projects can vary from 50 to hundreds of acres. Currently, there are more than 600 SEZ under construction in India which gives a good idea of the huge developing activity taking place in India with this system of colonizing undeveloped space.

Finally, the third engine of development is the creation of infrastructures by the private sector through grants to operate and exploit them for a certain period. This system is being used for the development of hard infrastructures like roads, airports, stations, desalinization plants, power plants, etc. but also soft infrastructures like hospitals or universities.

Given these three new urban grid growth models, we find a completely new model from the typological point of view.

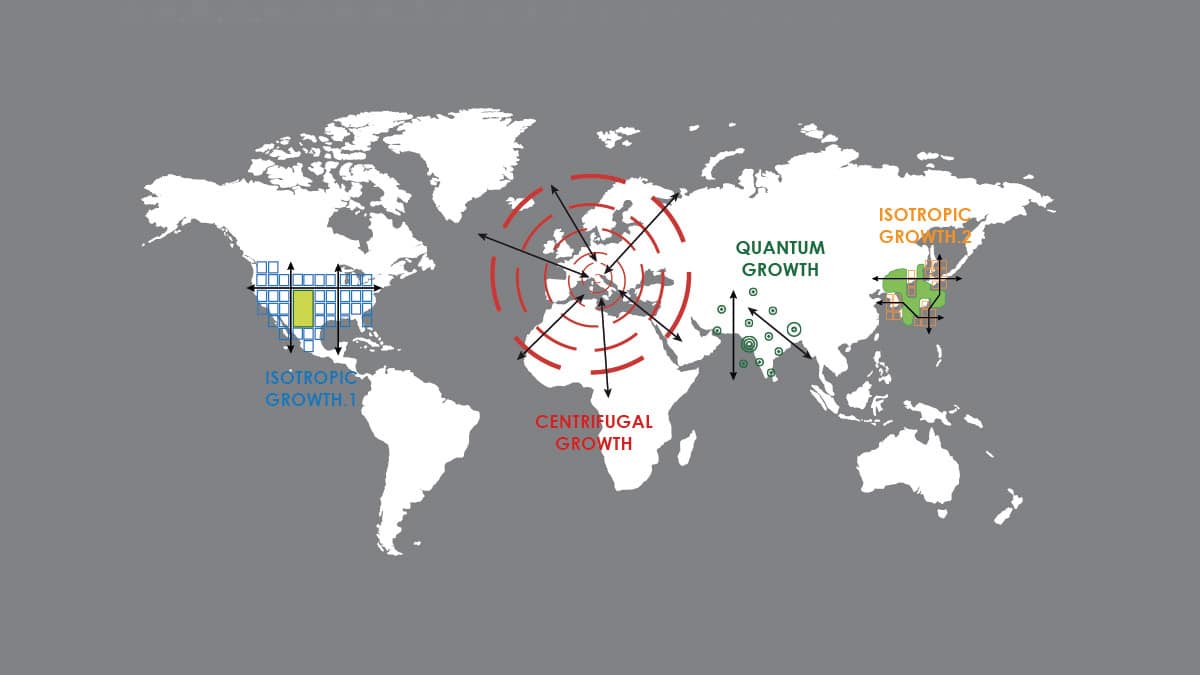

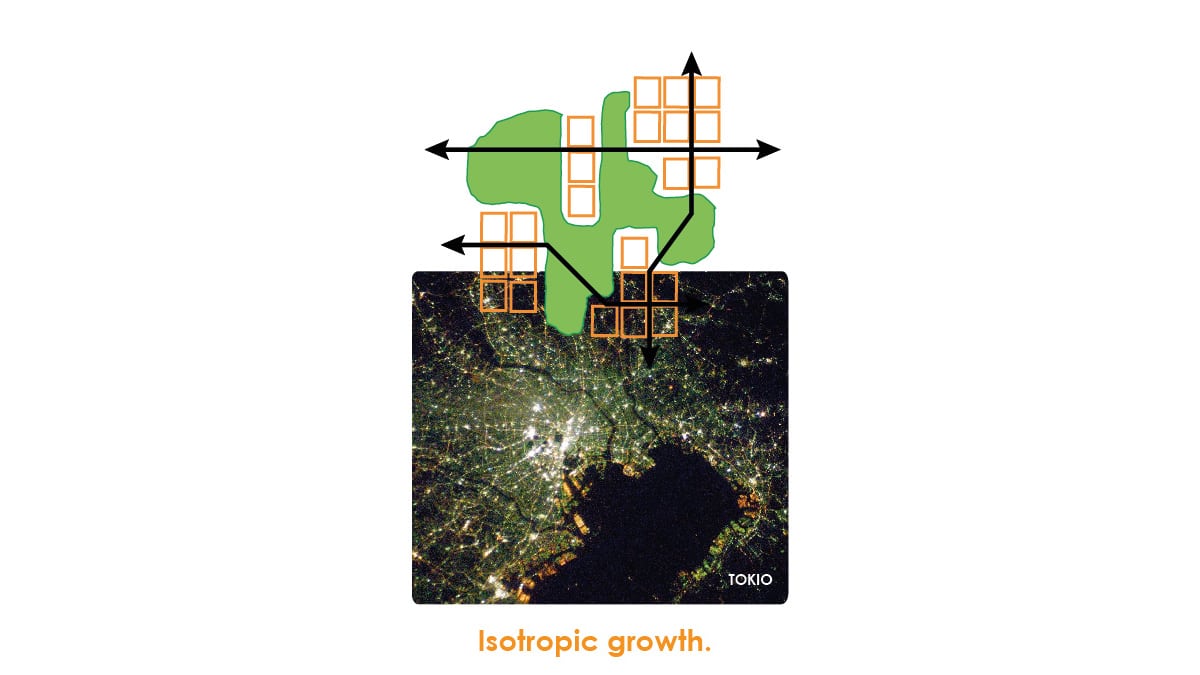

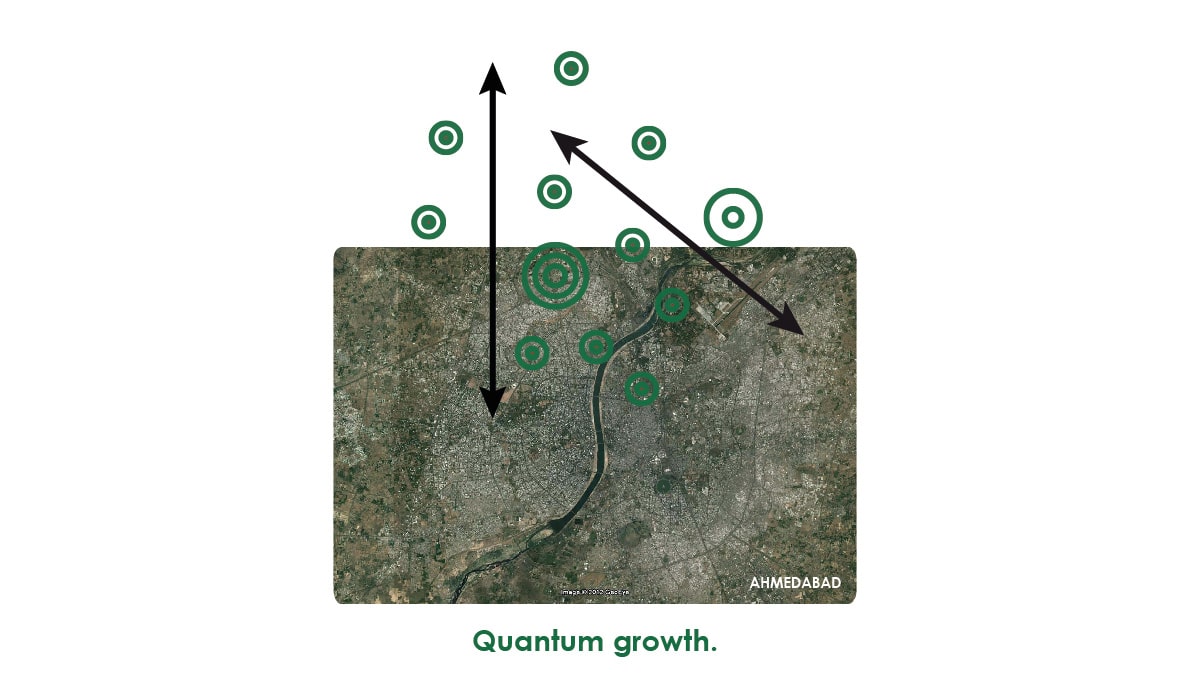

Summarizing urban evolution through History, we find four types of growth, which are also viually explained in the images on this article:

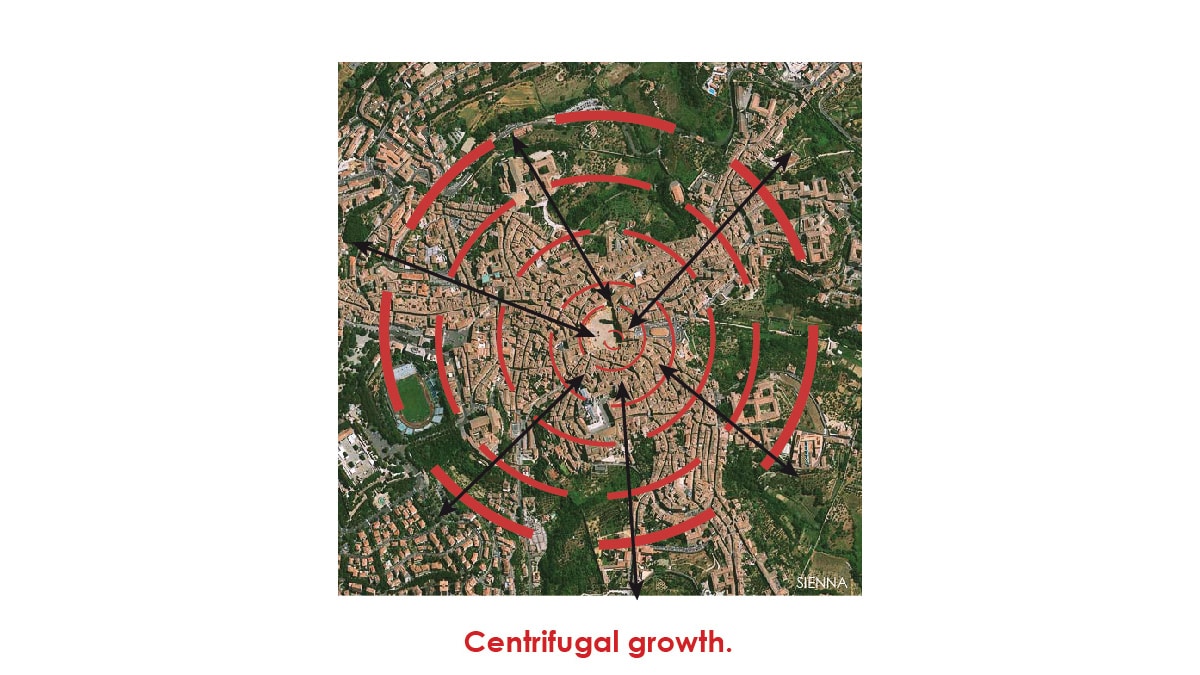

- Centrifugal growth around a center. Corresponds to typical patterns of growth of the traditional European city, where urban expansion happens in a more or less radial form, around a predetermined center, or a downtown.

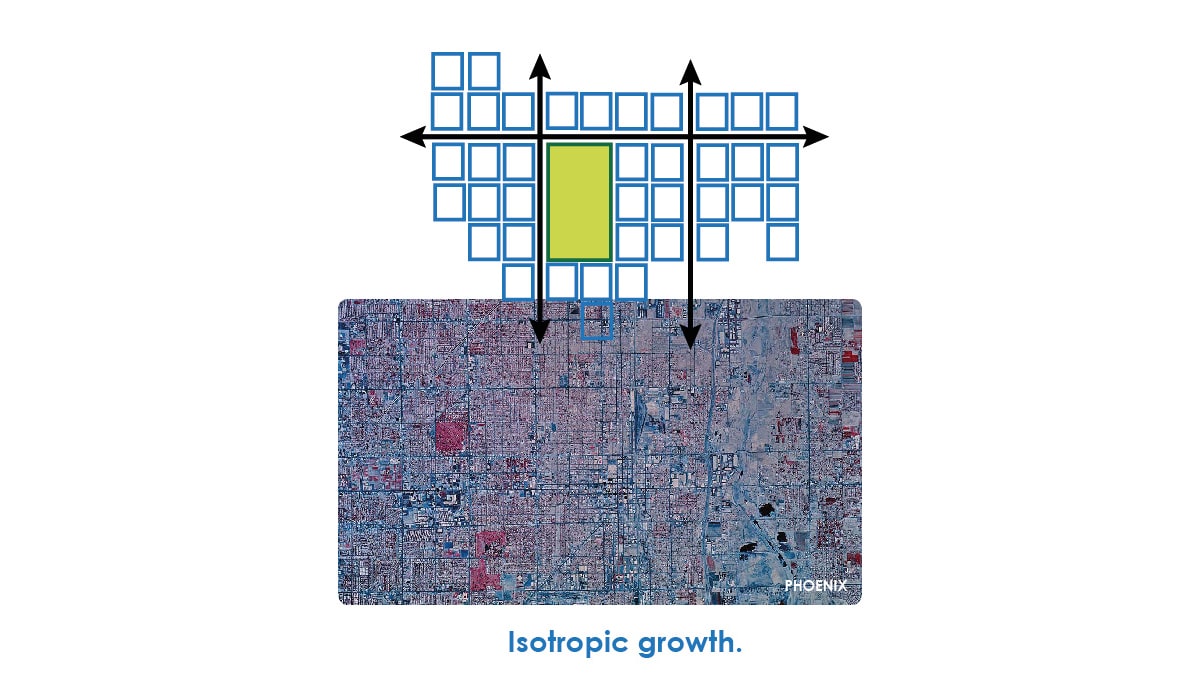

- Isotropic growth. No center. Corresponds to an urban model that started in the suburban expansion of North America, where a large number of developments are connected by infrastructural networks (roads) that rely on private transportation (cars). This urban model lacks a proper center.

- Isotropic growth. Multiple centers. The second isotropic growth model can be found in many urban solutions in Japan after the Second World War. This exciting urban model offers multiple centers that are equally important. Those centers are strongly connected by major infrastructure and green areas, establishing an isotopic network connecting urban nodes. The connectivity, in this case, is achieved by a strong public transport network.

- Quantum growth. Corresponds to the new patterns of growth in India and other developing countries, where the nodes are the infrastructures themselves (SEZ, townships, airports, etc) and such points are connected arbitrarily or even are kept separated from the big city networks, due to the lack of overall planning, the financial pressure, and the speed of execution of such nodes. This new typology offers a disjointed network of micro-autonomous cities. The separation mentioned above between governmental regulation and private sector pressure is one of the main causes of this new typology, which emphasizes the concept of “non-places” or “free denomination” mentioned at the beginning of this text.

The detailed study of this new type of settlement typical of emerging countries and specifically of India is interesting and offers opportunities to identify a new model of a city.

South European culture historically had a decisive importance in the settlement of urban patterns at a global level. From urban growth patterns of the Roman Empire, through the renaissance and baroque ideals, or the strong influence of garden cities and grid cities of the 19th Century, the ideas of Italian and Spanish Urban planning have always been considered revolutionary and have been exported all over the world due to their quality and theoretical and practical depth.

From our office in Spain, ABIBOO Studio has been working recently on the design of entire townships in India, and we identified a new pattern of urban growth that has completely new features and has not yet achieved a precise and accurate model to satisfy all the needs that arise.

The opportunity to define in detail those needs, along with the new forms of growth, will give the chance to apply the historical experience of South European urban theories in a global context to provide new solutions to 21st-century planning in emerging countries. It is in the hands of developers and urban planners to meet this important need of today.

Por los momentos esta publicación está disponible únicamente en inglés; lamentamos las molestias ocasionadas.